Fifty years ago, an Oakland community college moved to the hills over strong student opposition. Nothing was ever the same.

Robin Buller

Aug. 20, 2023 (SFChronicle.com)

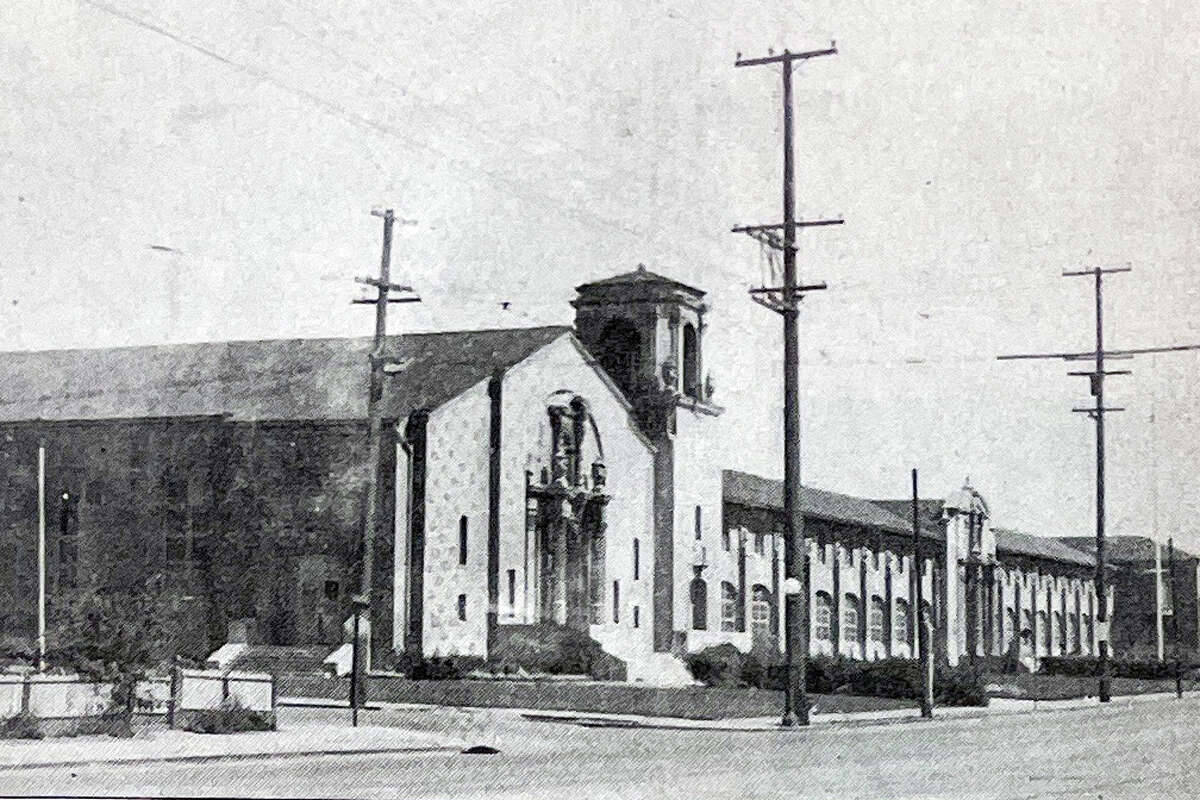

On Jan. 4, 1972, a vocal crowd sat in the audience of the Peralta Community College District board meeting in Oakland. It was made up of students and community members who, for several months, had been attending the biweekly meetings to express their disapproval of the board’s intention to close Merritt College’s North Oakland campus, located at 5714 Grove St. (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way).

The previous fall, most of the community college’s programs had been relocated to a sprawling plot on Campus Drive in the east Oakland hills. The hills site had some attractive features. Its numerous buildings were state-of-the-art new construction. And, with 125 acres, the campus would provide the college much-needed room to grow.

But the move also geographically severed the college from the community it primarily served.

In the early 1970s, the Oakland hills were suburban, wealthy, inaccessible by public transit and predominantly white. Grove Street, by way of contrast, was situated in the heart of the working-class and predominantly Black flatlands, where an influx of migrants who fled racial violence and bigotry in the American South had resettled beginning in the 1940s.

Over the course of the 1950s and ’60s, Merritt College became a transformative resource for the surrounding community, as well as a center for young civil rights activists. The college’s pink stucco walls inaugurated one of the nation’s first African American Studies programs, had a robust Black Students Union, and were where students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, the co-founders of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, met in fall 1966.

“Everybody wanted to be there. It was a very festive community atmosphere,” said Seale’s cousin Malcolm Westbrooks, who attended the college from 1969 to 1971, playing football and taking courses in both Swahili and Black history.

“Whether you were a panther or not, we were all activists” at Merritt, added Westbrooks, who never joined the party. “We lost that when it moved to the hills.”

Andrew Klein, a UCLA doctoral student researching the history of urban development in the Bay Area, describes Merritt as the lifeblood of a community. “Merritt College was always deeply woven into the fabric of North Oakland. It was a resource for people who didn’t even go to it,” he said, alluding to the many activists who used the campus for meeting, organizing and recruitment purposes.

Faced with the prospect of losing that hub, students called on administrators to find an alternate site nearby, but to no avail. In 1971, the hills campus opened its doors and, after a brief period of overlap, the North Oakland location was permanently shuttered in 1975. As a result, an important engine of upward mobility and center of Black activism was sealed off.

Today, with the Supreme Court overturning affirmative action, college campuses acting as ground zero for conservative culture wars and community college enrollment continuing its pandemic freefall, that history represents one chapter in a decades-long narrative about the links between equitable access to higher education and the pursuit of racial justice.

The hills have ayes

Merritt’s relocation did not happen overnight. Plans were in the works for nearly a decade, largely because of space. Over the course of the 1960s, the student body had rapidly outgrown the original building’s capacity, and by the end of the decade portable classrooms littered its courtyard. “The class bell at Merritt signals an explosion of bodies into the hallways,” read a 1965 article in the Oakland Tribune, “and anyone foolish enough to try to retrieve a dropped pencil faces the danger of becoming indelibly imprinted into the flooring.”

But that soaring enrollment also spoke to the community college’s appeal. Students, especially those from lower-income households, or who may have also had part-time jobs or family responsibilities, were drawn to the prospect of receiving a high-quality affordable education at their front door. With its exceptionally high transfer rate, Merritt College acted as a virtual feeder school for UC Berkeley up the street. Plus, the community college — like all California public colleges and universities — was tuition-free for state residents, a policy that all but ended with the enactment of per-unit fees in the late ’70s.

Administrators claimed that they sought out suitable replacement sites in and around North Oakland, but critics of the hill campus were not convinced that other options were considered in earnest. At one point, planners considered a site near the Berkeley waterfront, but tabled it in favor of Campus Drive.

Racism was also a factor. In “Living for the City,” a book about how students at East Bay colleges shaped the Black Power movement, historian Donna Murch writes that Grove Street’s reputation as a nucleus of Black radicalism coaxed white anxieties, causing administrative “backlash” and likely accelerating the move.

A Wall Street Journal article described Merritt as crime-ridden, dangerous, virtually devoid of pedagogy, and “located in one of (Oakland’s) sprawling Black slums”; an Oakland Tribune article claimed “Blacks aim for control at Merritt”; and Arthur Flegal, a local politician who later became mayor of Piedmont, a historically white East Bay city encircled by Oakland and formed through redlining, publically encouraged his colleagues to visit the North Oakland campus and “see if this is the place you want your daughter to take a course.”

“There was basically a line of demarcation separating the segregated flatlands from the more prosperous hill areas,” said Klein, the doctoral student. Moving to the hills, it was understood, would mean resituating the college in a white part of town and — proponents hoped — neutering some of the social movements, most notably the Black Panther Party, with which Grove Street had close ties.

That the student body did not approve of the relocation was clear. In spring 1970, a school survey revealed that students voted 2 to 1 to remain in the flatlands. Then, in fall 1971, a group of 90 students demanding the campus remain under “community control” occupied the office of the college president for several hours and had to be forcibly removed by Oakland police.

Even some faculty were against the move. Westbrooks, the alumnus, recalls that one of his professors refused to teach his “Black Church in the Community” course in the hills, and instead taught it in an empty storefront in the flatlands for a year before resigning. “It was like his private protest,” said Westbrooks.

Still, the move went forward, and when classes were offered at the new hills campus, the resentment was palpable. Jeanette Medis, a single mother and student at Grove Street, told a reporter that the relocation meant she would need to quit school and go on welfare. The college’s weekly newspaper lamented that the relocation had caused student participation in campus clubs and extracurriculars to virtually disintegrate. Another simply called the new site “this often hated hill.”

But it remained a critical resource for those Black Oaklanders who were able to make the commute, including the family of David Johnson, the current president of Merritt College. Johnson’s mother attended Merritt after it had relocated to the hill campus, and he remembers doing his homework in its library while she attended class. “It was a game changer for our family in terms of changing our socioeconomic status,” he said.

Saturu Ned, a Black Panther Party alumnus, said the party organized carpools so that students who lived in the flatlands could keep going to class, but the loss of the North Oakland campus left an irreparable scar.

“Removing it removed a means of education from the community,” he said.

Priorities on campus did change following the move. The renowned African American Studies program, for instance, suffered from a lack of funding; by 1982 — the same year the Black Panther Party dissolved — the program ostensibly hadn’t made a new hire in a decade.

Legacy, admissions

Today, Merritt boasts a sizable and diverse student body, curricula that are prized among public community colleges, a direct-to-campus bus route from the nearest BART station (which is still 4 miles away), and sweeping views of San Francisco Bay.

But its expansive location also tells a larger story about the geographies of higher education and the impact of institutions’ desires for unbridled room to expand.

After the North Oakland campus closed in 1974, says Klein, the area’s residents lost a resource that had been uniquely valuable. Since then, Black Oaklanders have been pushed out of the neighborhood, which is today one of the city’s most expensive areas. Whereas in 1980, the area around Merritt’s North Oakland campus was 88% Black, that figure had dropped to 26% by 2020, mirroring a larger Black exodus out of the Bay Area in recent decades.

“That’s an enormous shift,” said Sephen Menendian, associate director of UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute, which operates a tool that uses census data to demonstrate the correlation between segregation and opportunity.

Merritt’s radical past is memorialized in the Huey P. Newton Student Lounge as well as the name of the school mascot, which was recently changed from the Thunderbird to the Panther.

But for James Lance Taylor, a professor of political science at the University of San Francisco who studies Black nationalism, those nods simplify a complex history, and mask the importance of the college’s original location to its social justice roots.

“I love that campus up there, but the politics of it, I’ve always felt, was actually a sellout,” Taylor said. “And that room dedicated to (Newton) is a confirmation of the sellout because it’s honoring them up there in Merritt in the hills, when the real struggle and the impetus for everything they were doing was at Grove Street.”

Although it is on a bus line, its peripheral location means that it is still more difficult for students to access than other community colleges in the Peralta District, such as Laney College and Berkeley City College, both of which can be reached by BART.

“Distance matters,” said Tolani Britton, a professor of education at UC Berkeley whose research focuses on college accessibility and retention. Britton says location is a top consideration when students of color choose a college, and that its importance is even more pronounced for those who seek to attend two-year institutions like Merritt.

One 2009 study showed that a distance of just 3 miles dramatically reduced whether students over age 25 — who are more likely to have families and jobs to consider — will enroll in a community college.

On top of that, a lack of affordable housing near Merritt’s campus in the hills — part of a larger cost-of-living crisis facing college students across the state — means many students are forced to commute long distances to attend class. Johnson, the college’s president, joins other community college leaders in pushing the state for funding to help build housing at a time when declining enrollment lingering from the COVID-19 pandemic is straining institutions’ finances, with many facing mergers or outright closure.

California’s community college system lost more than 318,000 students between 2019 and 2021, of which 47% were Latino, 20% were Native American and 16% were Black. Nationally, enrollment for Black students declined by 18% during those same years.

Merritt’s numbers reveal a similar pattern. Its total enrollment fell more than 8% from 6,857 in fall 2019 to 6,289 in fall 2021, and the Black student population alone dropped a disproportional 14% from 1,538 to 1,322. Since fall 2022, Merritt and the other Peralta colleges have worked to draw back students by offering free tuition.

On a Wednesday in April, college president Johnson walked past a vacant parking lot and into a library furnished with empty study tables, lamenting that the campus in the hills had been quiet since classes first went remote at the start of the pandemic. He believes having students live in the surrounding community could be a crucial step toward not only boosting enrollment, but also revitalizing campus life.

Doing so, he hopes, could also revive some of the dynamics that made the flatlands campus — now a research facility for UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland — such a valuable community resource in the ’60s.

“One of the virtues of the Grove Street campus is you had people in that community … availing themselves of this tremendous opportunity,” Johnson said. “I’m going back to that idea of Merritt being the locus of political justice and academic excellence. I’m trying to re-establish that connection.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the affiliation of James Lance Taylor. He is a political science professor with the University of San Francisco.

Robin Buller is a journalist based in Oakland. Twitter: @RobinBuller

Written By Robin Buller