From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For his eldest son, a lawyer and Member of Parliament, see William Wilberforce (1798–1879).

| William Wilberforce | |

|---|---|

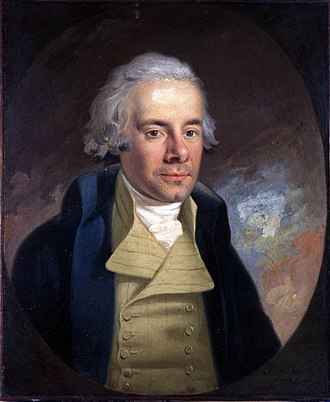

| William Wilberforce by Karl Anton Hickel, c. 1794 | |

| Member of Parliament | |

| In office 31 October 1780 – February 1825 | |

| Preceded by | David Hartley |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Gough-Calthorpe |

| Constituency | Kingston upon Hull (1780–1784)Yorkshire (1784–1812)Bramber (1812–1825) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 August 1759 Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 29 July 1833 (aged 73) Belgravia, London, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Barbara Spooner (m.1797) |

| Children | 6, including Robert, Samuel and Henry |

| Alma mater | St John’s College, Cambridge |

| Signature | |

| Venerated in | Anglicanism |

| Feast | 30 July |

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, and became an independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Yorkshire (1784–1812). In 1785, he underwent a conversion experience and became an Evangelical Anglican, which resulted in major changes to his lifestyle and a lifelong concern for reform.

In 1787, Wilberforce came into contact with Thomas Clarkson and a group of activists against the slave trade, including Granville Sharp, Hannah More and Charles Middleton. They persuaded Wilberforce to take on the cause of abolition, and he became a leading English abolitionist. He headed the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for 20 years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807.

Wilberforce was convinced of the importance of religion, morality and education. He championed causes and campaigns such as the Society for the Suppression of Vice, British missionary work in India, the creation of a free colony in Sierra Leone, the foundation of the Church Mission Society and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He supported politically and socially repressive legislation. His critics thought that he was ignoring injustices at home while campaigning for the enslaved abroad.

In later years, Wilberforce supported the campaign for the complete abolition of slavery and continued his involvement after 1826, when he resigned from Parliament because of his failing health. That campaign led to the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which abolished slavery in most of the British Empire. Wilberforce died just three days after hearing that the passage of the act through Parliament was assured. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to his friend William Pitt the Younger.

Early life and education

Wilberforce was born in Hull, in Yorkshire, England, on 24 August 1759.[1] He was the only son of Robert Wilberforce (1728–1768), a wealthy merchant, and his wife, Elizabeth Bird (1730–1798). His grandfather, William (1690–1774),[2][3] had made the family fortune in the maritime trade with Baltic countries.[a][4] He was twice elected mayor of Hull.[5]

Wilberforce was a small, sickly and delicate child with poor eyesight.[6] In 1767, he began attending Hull Grammar School,[7] which at the time was headed by Joseph Milner, who would become a lifelong friend.[8] Wilberforce profited from the supportive atmosphere at the school, until his father died in 1768. With his mother struggling to cope, the nine-year-old Wilberforce was sent to a prosperous uncle and aunt with houses in both St James’s Place, London, and Wimbledon. He attended an “indifferent” boarding school in Putney for two years and spent his holidays in Wimbledon, where he grew extremely fond of his relatives.[9] He became interested in evangelical Christianity due to his relatives’ influence, especially that of his aunt Hannah, sister of the wealthy merchant John Thornton, a philanthropist and a supporter of the leading Methodist preacher George Whitefield.[1]

Wilberforce’s staunchly Church of England mother and grandfather, alarmed at these nonconformist influences and at his leanings towards evangelicalism, brought the 12-year-old boy back to Hull in 1771. Wilberforce was heartbroken at being separated from his aunt and uncle.[10] His family opposed a return to Hull Grammar School because the headmaster had become a Methodist, and Wilberforce continued his education at Pocklington School from 1771 to 1776.[11][12] Influenced by Methodist scruples, he initially resisted Hull’s lively social life, but, as his religious fervour diminished, he embraced theatre-going, attended balls, and played cards.[13]

In October 1776, at the age of seventeen, Wilberforce went up to St John’s College, Cambridge.[14] The deaths of his grandfather and uncle, in 1774 and 1777 respectively, had left him independently wealthy[15] and as a result he had little inclination or need to apply himself to serious study. Instead he immersed himself in the social round of student life[14][15] and pursued a hedonistic lifestyle, enjoying cards, gambling and late-night drinking sessions – although he found the excesses of some of his fellow students distasteful.[16][17] Witty, generous and an excellent conversationalist, Wilberforce was a popular figure. He made many friends, including the more studious future Prime Minister William Pitt.[17][18] Despite his lifestyle and lack of interest in studying, he managed to pass his examinations[19] and was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1781 and a Master of Arts degree in 1788.[1]

Early parliamentary career

Wilberforce began to consider a political career while still at university and during the winter of 1779–1780, he and Pitt frequently watched House of Commons debates from the gallery. Pitt, already set on a political career, encouraged Wilberforce to join him in obtaining a parliamentary seat.[19][20] In September 1780, at the age of 21 and while still a student, Wilberforce was elected Member of Parliament for Kingston upon Hull,[1] spending over £8,000, as was the custom of the time, to ensure he received the necessary votes.[21][22] Free from financial pressures, Wilberforce sat as an independent, resolving to be “no party man”.[1][23] Criticised at times for inconsistency, he supported both Tory and Whig governments according to his conscience, working closely with the party in power, and voting on specific measures according to their merits.[24][25]

Wilberforce attended Parliament regularly, but he also maintained a lively social life, becoming an habitué of gentlemen’s gambling clubs such as Goostree’s and Boodle’s in Pall Mall, London. The writer and socialite Madame de Staël described him as the “wittiest man in England”[26] and, according to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, the Prince of Wales said that he would go anywhere to hear Wilberforce sing.[27][28] Wilberforce used his speaking voice to great effect in political speeches; the diarist and author James Boswell witnessed Wilberforce’s eloquence in the House of Commons and noted, “I saw what seemed a mere shrimp mount upon the table; but as I listened, he grew, and grew, until the shrimp became a whale.”[29]

During the frequent government changes of 1781–1784, Wilberforce supported his friend Pitt in parliamentary debates.[30] In autumn 1783, Pitt, Wilberforce and Edward Eliot travelled to France for a six-week holiday together.[1] After a difficult start in Rheims, where their presence aroused police suspicion that they were English spies, they visited Paris, meeting Benjamin Franklin, General Lafayette, Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, and joined the French court at Fontainebleau.[31]

Pitt became Prime Minister in December 1783, with Wilberforce a key supporter of his minority government.[32] Despite their close friendship, there is no record that Pitt offered Wilberforce a ministerial position in this or future governments. This may have been due to Wilberforce’s wish to remain an independent MP. Alternatively, Wilberforce’s frequent tardiness and disorganisation, as well as his chronic eye problems that at times made reading impossible, may have convinced Pitt that he was not ministerial material.[33] When Parliament was dissolved in the spring of 1784, Wilberforce decided to stand as a candidate for the county of Yorkshire in the 1784 general election.[1] On 6 April, he was returned as MP for Yorkshire at the age of twenty-four.[34]

Conversion

In October 1784, Wilberforce embarked upon a tour of Europe with his mother, sister and Isaac Milner, the younger brother of his former headmaster. They visited the French Riviera and had dinners, played cards, and gambled.[35] In February 1785, Wilberforce returned to London temporarily, to support Pitt’s proposals for parliamentary reforms. He rejoined the party in Genoa, Italy, and they continued their tour to Switzerland. Milner accompanied Wilberforce to England, and on the journey they read “The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul” by Philip Doddridge, a leading early 18th-century English nonconformist.[36]

Wilberforce’s spiritual journey is thought to have changed course at this time. He started to rise early to read the Bible and pray and kept a private journal.[37] He underwent an evangelical conversion, regretting his past life and resolving to commit his future life and work to the service of God.[1] His conversion changed some of his habits, but not his nature: he remained outwardly cheerful, interested and respectful, tactfully urging others towards his new faith.[38] Inwardly, he became self-critical, harshly judging his spirituality, use of time, vanity, self-control and relationships with others.[39]

At the time, religious enthusiasm was generally regarded as a social transgression and was stigmatised in polite society. Evangelicals in the upper classes were exposed to contempt and ridicule,[40] and Wilberforce’s conversion led him to question whether he should remain in public life. He sought guidance from John Newton, a leading evangelical Anglican clergyman of the day and Rector of St Mary Woolnoth.[41][42] Both counselled him to remain in politics, and he resolved to do so “with increased diligence and conscientiousness”.[1] His political views were informed by his faith and by his desire to promote Christianity and Christian ethics in private and public life.[43][44] His views were often deeply conservative, opposed to radical changes in a God-given political and social order, and focused on issues such as the observance of the Sabbath and the eradication of immorality through education and reform.[45] He was often distrusted by progressive voices because of his conservatism, and regarded with suspicion by many Tories who saw evangelicals as radicals who wanted the overthrow of church and state.[25]

In 1786, Wilberforce leased a house in Old Palace Yard, Westminster, in order to be near Parliament. He began using his parliamentary position to advocate reform by introducing a Registration Bill, proposing limited changes to parliamentary election procedures.[1][46] In response to the need for bodies for dissection by surgeons, he brought forward a bill to extend the measure permitting the dissection after execution of criminals such as rapists, arsonists, burglars and violent robbers. The bill also advocated the reduction of sentences for women convicted of treason, a crime that at the time included a husband’s murder. The House of Commons passed both bills, but they were defeated in the House of Lords.[47][48][49]

Abolition of the transatlantic slave trade

Initial decision

The British initially became involved in the slave trade during the 16th century. By 1783, the triangular route that took British-made goods to Africa to buy slaves, transported the enslaved to the West Indies, and then brought slave-grown products such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton to Britain, represented about 80 percent of Great Britain’s foreign income.[50][51] British ships dominated the slave trade, supplying French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and British colonies, and in peak years carried forty thousand enslaved men, women and children across the Atlantic in the horrific conditions of the middle passage.[52] Of the estimated 11 million Africans transported into slavery, about 1.4 million died during the voyage.[53]

The British campaign to abolish the slave trade is generally considered to have begun in the 1780s with the establishment of the Quakers‘ anti-slavery committees, and their presentation to Parliament of the first slave trade petition in 1783.[54][55] The same year, Wilberforce, while dining with his Cambridge friend Gerard Edwards,[56] met Rev. James Ramsay, a ship’s surgeon who had become a clergyman and medical supervisor on the island of St Christopher (later St Kitts). Ramsay was horrified by the conditions endured by the enslaved peoples, both at sea and on the plantations and returned to England and joined abolitionist movements.[57] Wilberforce did not follow up on his meeting with Ramsay,[56] but three years later, inspired by his new faith, Wilberforce became interested in humanitarian reform. In November 1786, he received a letter from Sir Charles Middleton that re-opened his interest in the slave trade.[58][59] Middleton suggested that Wilberforce bring forward the abolition of the slave trade in Parliament. Wilberforce responded that he “felt the great importance of the subject, and thought himself unequal to the task allotted to him, but yet would not positively decline it”.[60] He began to read widely on the subject and met with a group of abolitionists called the Testonites at Middleton’s home in the early winter of 1786–1787.[61]

In early 1787, Thomas Clarkson met with Wilberforce for the first time at Old Palace Yard and brought a copy of his essay on the subject.[62][63][64] Clarkson visited Wilberforce weekly, bringing first-hand evidence he had obtained about the slave trade.[63][65] The Quakers, already working for abolition, recognised the need for influence within Parliament, and urged Clarkson to secure a commitment from Wilberforce to bring forward the case for abolition in the House of Commons.[66][67] It was arranged that Bennet Langton, a Lincolnshire landowner and mutual acquaintance of Wilberforce and Clarkson, would organise a dinner party on 13 March 1787 to ask Wilberforce formally to lead the parliamentary campaign.[68] By the end of the evening, Wilberforce had agreed in general terms that he would bring forward the abolition of the slave trade in Parliament, “provided that no person more proper could be found”.[69]

The same spring, on 12 May 1787, the still hesitant Wilberforce held a conversation with William Pitt and the future Prime Minister William Grenville as they sat under a large oak tree on Pitt’s estate in Kent.[1] Under what came to be known as the “Wilberforce Oak” at Holwood House, Pitt challenged his friend to give notice of a motion concerning the slave trade before another parliamentarian did.[70] Wilberforce’s response is not recorded, but he later declared this was when he decided to bring forward the motion.[71]

Early parliamentary action

Wilberforce had planned to introduce a motion giving notice that he would bring forward a bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade during the 1789 parliamentary session. However, in January 1788, he was taken ill with a probable stress-related condition, now thought to be ulcerative colitis.[72][73] It was several months before he was able to resume work, and he spent time convalescing at Bath and Cambridge. His regular bouts of gastrointestinal illnesses precipitated the use of moderate quantities of opium, which proved effective in alleviating his condition,[74] and which he continued to use for the rest of his life.[75] In Wilberforce’s absence, Pitt, who had long been supportive of abolition, introduced the preparatory motion himself, and ordered a Privy Council investigation into the slave trade, followed by a House of Commons review.[76][77]

With the publication of the Privy Council report in April 1789 and following months of planning, Wilberforce commenced his parliamentary campaign.[74][78] On 12 May 1789, he made his first major speech on the subject of abolition in the House of Commons, in which he reasoned that the trade was morally reprehensible and an issue of natural justice. Drawing on Thomas Clarkson’s mass of evidence, he described in detail the appalling conditions in which enslaved people travelled from Africa in the middle passage and argued that abolishing the trade would also bring an improvement to the conditions of existing slaves in the West Indies. He moved twelve resolutions condemning the slave trade, but did not refer to the abolition of slavery itself, instead dwelling on the potential for reproduction in the existing slave population should the trade be abolished.[79][80] With several parliamentarians signalling support for the bill, the opponents of abolition delayed the vote by proposing that the House of Commons hear its own evidence; Wilberforce, in a decision that has been criticised for prolonging the slave trade, reluctantly agreed.[81][82] The hearings were not completed by the end of the parliamentary session and were deferred until the following year. In the meantime, Wilberforce and Clarkson tried unsuccessfully to take advantage of the egalitarian atmosphere of the French Revolution to press for France’s abolition of the trade.[83] In January 1790, Wilberforce succeeded in speeding up the hearings by gaining approval for a smaller parliamentary select committee to consider the vast quantity of evidence which had been accumulated.[84] Wilberforce’s house in Old Palace Yard became a centre for the abolitionists’ campaign and the location for many strategy meetings.[1] Petitioners for other causes also besieged him there.[85][86][87]

Let us not despair; it is a blessed cause, and success, ere long, will crown our exertions. Already we have gained one victory; we have obtained, for these poor creatures, the recognition of their human nature, which, for a while was most shamefully denied. This is the first fruits of our efforts; let us persevere and our triumph will be complete. Never, never will we desist till we have wiped away this scandal from the Christian name, released ourselves from the load of guilt, under which we at present labour, and extinguished every trace of this bloody traffic, of which our posterity, looking back to the history of these enlightened times, will scarce believe that it has been suffered to exist so long a disgrace and dishonour to this country.

William Wilberforce — speech before the House of Commons, 18 April 1791[88]

Interrupted by a general election in June 1790, the committee finished hearing witnesses and in April 1791, with a closely reasoned four-hour speech, Wilberforce introduced the first parliamentary bill to abolish the slave trade.[89][90] After two evenings of debate, the bill was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88, as the political climate having swung in a conservative direction after the French Revolution and in reaction to an increase in radicalism and to slave revolts in the French West Indies.[91][92]

A protracted parliamentary campaign to abolish slavery continued, and Wilberforce remained committed to this cause despite frustration and hostility. He was supported by fellow members of the Clapham Sect, among whom was his best friend and cousin Henry Thornton.[93][94] Wilberforce accepted an invitation to share a house with Henry Thornton in 1792, moving into his own home after Thornton’s marriage in 1796.[95] Wilberforce, the Clapham Sect and others were anxious to demonstrate that Africans, and particularly freed slaves, had human and economic abilities beyond the slave trade and capable of sustaining a well-ordered society, trade and cultivation. Inspired in part by the utopian vision of Granville Sharp, they became involved in the establishment in 1792 of a free colony in Sierra Leone with black settlers from Britain, Nova Scotia and Jamaica, as well as native Africans and some whites.[96][97] They formed the Sierra Leone Company, with Wilberforce subscribing liberally to the project in money and time.[98]

On 2 April 1792, Wilberforce brought another bill calling for abolition of the slave trade.[99] Henry Dundas, as Home Secretary, proposed a compromise solution of gradual abolition of the trade over several years. This was passed by 230 to 85 votes, but Wilberforce believed that it was little more than a clever ploy to ensure that total abolition would be delayed indefinitely.[100][101]