See the path from arrest to removal for immigrants detained by ICE in the Bay

by KELLY WALDRON and FRANKIE SOLINSKY DURYEA

July 30, 2025 (MissionLocal.org)

In early July, Edin Eduardo Castañeda Reyes stopped to get breakfast on his way to work in Redwood City when he noticed two unmarked cars following him into the parking lot.

“Right when I got out of my car and took two steps, they were on top of me, telling me not to move,” the 24-year-old Reyes said in Spanish in a telephone interview from Guatemala.

One of the three uniformed Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers asked for his driver’s license and then quickly cuffed him. They took his car keys and phone, Reyes said, and left his backpack in his car.

By 7 a.m. on that July 14 morning, Reyes, who had been living in the United States since 2016, was on his way to an ICE processing center.

Years earlier, Reyes had missed a court date for immigration proceedings in 2018. He knew that a removal order had been signed against him. But, while ICE officers had taken neighbors in the past, he had never been targeted.

Besides, he was married to an American citizen, Angela, and they had two children, ages 2 and 4.

Angela learned of her husband’s arrest through a video on NextDoor. It showed Reyes standing in the parking lot, surrounded by ICE agents.

Mission Local has documented dozens of ICE arrests that have taken place in San Francisco since May 27, 2025. Data, however, indicates there are far more detentions in what is known as the “San Francisco Area of Responsibility,” which covers Northern California, Hawaii, Guam, and Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands.

At least 87 percent of those arrests were in the state of California.

By cross-referencing three datasets released this month — on ICE arrests, detentions and deportations — Mission Local was able to follow the journeys of those arrested between Jan. 20 and June 26 in this “Area of Responsibility.”

No names are attached to the datasets, but each person has a unique identification number. Using that number, we can plot each journey from arrest to deportation or release.

The data from Jan. 20 to June 26 was made available through records requests and subsequent litigation from the Deportation Data project, a group of researchers headed by David Hausman the University of California, Berkeley.

The data shows that arrests in the San Francisco “Area of Responsibility” have doubled compared to last year. They increased even more in late May, when senior officials from the White House ordered ICE to reach a quota of 3,000 arrests per day.

ICE arrests shot up in the S.F. area in 2025

This includes administrative arrests — arrests for civil violations of immigration law — within the San Francisco Area of Responsibility by week. That jurisdiction includes Northern California, Hawaii, Guam and Saipan. Data from the Deportation Data Project. Chart by Kelly Waldron.

ICE’s annual budget was recently increased from $8 billion to $28 billion, and attorneys are worried that this change in funds will lead to even more arrests, wrote Jennifer Friedman, interim manager of the Immigration Unit at the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office.

“It’s definitely heading in that direction,” Friedman wrote.

Most arrests in the city of San Francisco have taken place at immigration court or at ICE check-ins, at 630 Sansome St. and 100 Montgomery St., two locations within the city where asylum seekers appear for regularly scheduled hearings. Arrests elsewhere are made in parking lots, homes and jails.

For 23-year-old Anibal Mauricio Martinez Molinas, the arrest happened at his apartment when three uniformed ICE agents appeared at his door in San Jose.

Martinez left El Salvador with a group of other immigrants, when he was 9. He was detained by border control while walking through the Sonoran desert.

Martinez managed to delay removal for the next 14 years while finishing school and working at tire shops. Along the way, he became as comfortable speaking in English as he was in Spanish, and started going by Michael rather than Miguel, he said in a phone interview from El Salvador.

His American life ended on the night of June 17, 2025. Officers showed Martinez papers confirming his detention at the border more than a decade ago, and the removal orders that followed. Martinez was too shocked to even read them. “It’s over,” he remembers thinking.

After letting the ICE agents enter his South Bay apartment, Martinez gathered some clothes, an empty backpack, two pairs of shoes, a medical device for a sleep disorder, his passport, and $4,500 in savings; $200 or so in cash, and the rest on his debit card.

“The whole time that I was over there” — in the United States — “I was just fighting for a life worth living,” said Martinez. “I was kind of starting to make good progress towards that. And then this happened.”

The agents handcuffed him, put him in a van and drove him to the closest processing center.

Reyes and Martinez are two of the 2,123 immigrants who have been arrested in the San Francisco “Area of Responsibility” since Jan. 20. Many, like Reyes and Martinez, have no criminal record beyond traffic fines, and had lived in the United States for years. Their arrests seemed to come out of nowhere.

ICE arrests between January 20, 2025 and June 26 in the San Francisco Area of Responsibility.

The vast majority of those people were sent to ICE detention centers across the state and country.

It is unclear whether the 66 remaining people were released, or are missing in detention records.

The rest were deported.

As of the end of June, 689 people remained in detention — and had been there for an average of 45 days.

One-hundred and eighteen people were released for various reasons. One detainee escaped, others left detention for “voluntary return” and others for reasons that are unclear.

Of those who were deported, most were deported to Mexico.

The rest were sent to 33 other countries. Records indicating the departure country are missing for 103 others.

TK TK TK

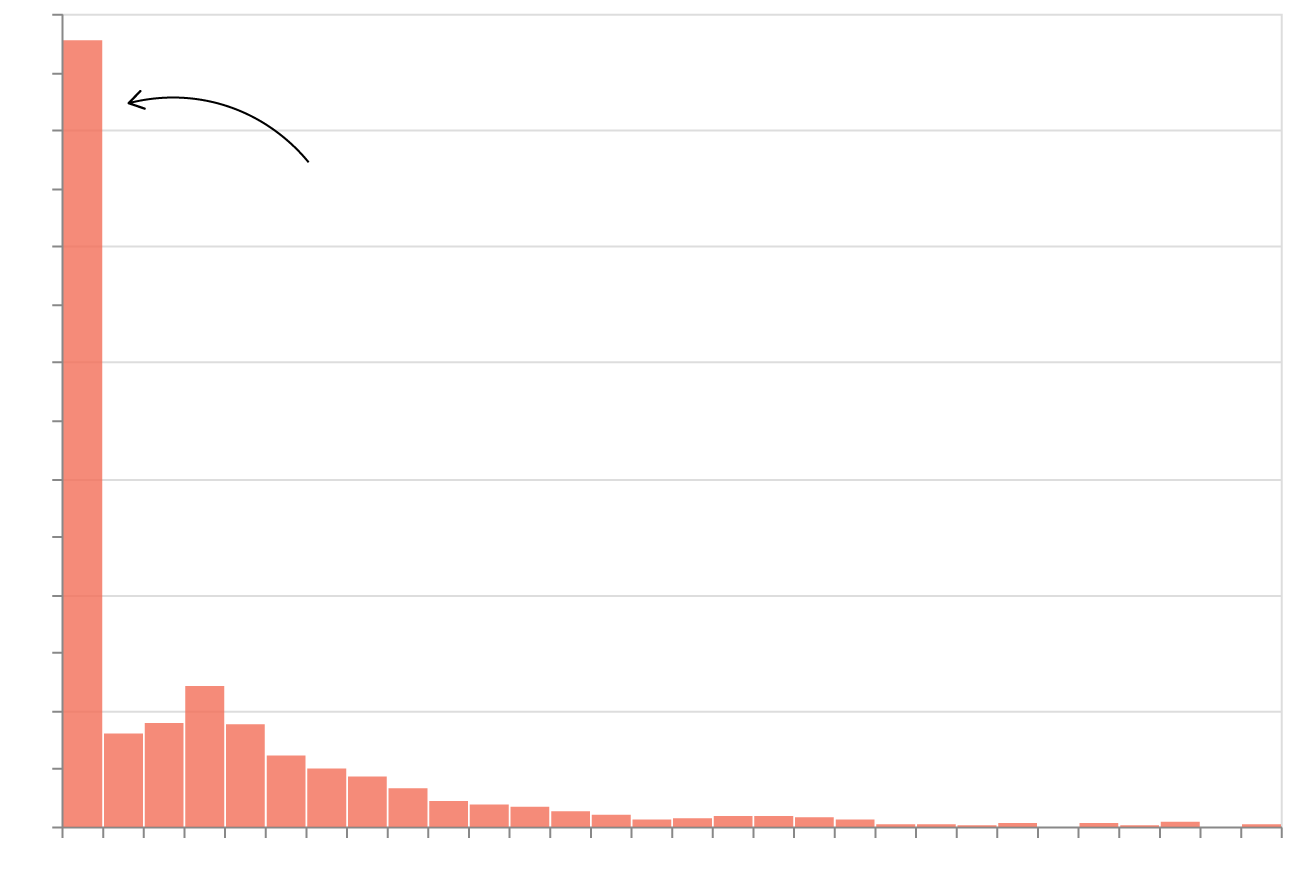

Most detainees are quickly shuffled through

Mission Local identified 2,057 of the 2,123 people arrested in the San Francisco “Area of Responsibility” in ICE detention records. As of the end of June, 689 of them remained in a detention facility.

Of the 1,368 individuals in our data who were released from detention or deported, about half of them had been held in ICE custody for fewer than six days. Some 270 were in detention for more than 30 days.

Most detainees are moved through the system quickly

Only includes detainees who were arrested in the San Francisco Area of Responsibility between January 20, 2025 and June 26, 2025 and released from ICE custody within that period. Data from the Deportation Data Project. Chart by Kelly Waldron.

Michael Martinez was one of the many immigrants who moved through removal proceedings in less than a day.

While Martinez said that he couldn’t remember which processing center he was in, the drive from San Jose took less than an hour, meaning it was most likely 630 Sansome St. in downtown San Francisco. There, he was fingerprinted and allowed to make a phone call.

Since Jan. 20, at least 433 people have been detained at 630 Sansome St. in the SFR Holdroom on the fourth floor of the same building that holds ICE offices and immigration courts. For most detainees, the hold room is the first stop following their arrest.

ICE agents put Martinez into a holding room with about five other men from Mexico and Colombia, he said. He was given a suitcase for his belongings, but was careful to put his debit card and cash into a pocket of his backpack.

Less than a month later, Edin Reyes passed through the same processing center at 630 Sansome St.

By the time Reyes got there around 8 a.m. on July 14, his hands hurt from how tightly his handcuffs had been put on, he said. Five hours later, agents again put him in a van and drove him to the Fresno Holding Center, a hotspot for short-term detentions that 602 people in our dataset passed through from Jan. 20 to June 26, 2025.

In Fresno, he said, agents pressured him into signing a paper authorizing his immediate deportation.

“Look, we’re going to deport you no matter what,” Reyes remembered being told. “You sign or you don’t sign. I have to deport you. So it’s better that you sign your removal now. It’ll be quicker.”

Reyes had no access to a lawyer, he said, and no one offered him a phone call. He signed the papers, and then fell asleep on the floor of the Fresno holding cell.

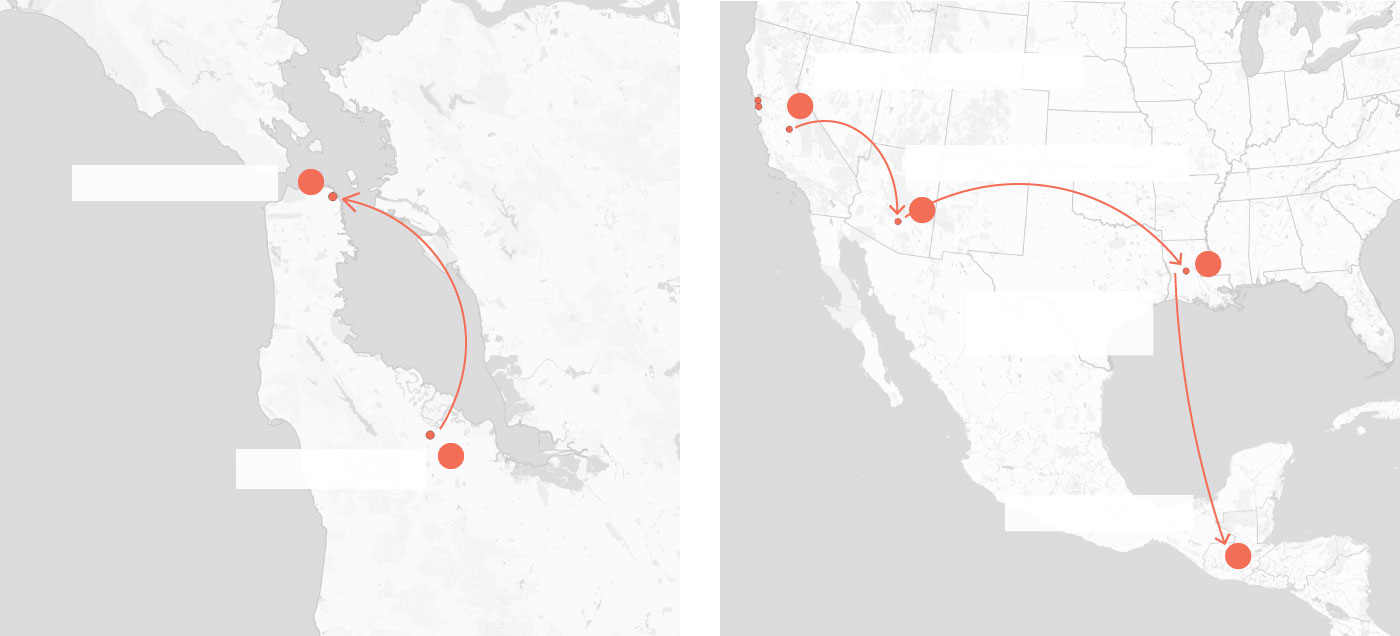

On average, the detainees in our analysis were transferred three times, typically from short-term “holding” or “staging” facilities to a larger detention center.

Those arrested in the S.F. area have landed in detention centers across the country

Data from the Deportation Data Project. This map includes “book ins” for detention stays among those who were arrested in the San Francisco Area of Responsibility since Jan. 20, 2025. Most detainees were booked in at multiple locations. The map only includes facilities that received three “book ins” or more.

Out of those arrested in the San Francisco “area of responsibility” this year who are no longer in ICE custody, the average time spent in detention was 16 days.

According to Jeff Migliozzi of the advocacy organization Freedom for Immigrants, the Trump administration’s expansion of expedited removal has allowed for much faster deportation proceedings, skirting prior guardrails for deportation. “They’re eliminating a crucial stage of due process,” said Migliozzi.

While Martinez’s stay in ICE detention was short, Reyes passed through several processing centers. The morning after he was detained, Reyes was flown from Fresno to the Florence Processing Center in Arizona, where some 151 immigrants arrested in the San Francisco area have ended up.

It was in Arizona that he was first given the opportunity to call his wife. As soon as she heard his voice, Angela said she knew “there was just nothing to do.”

The next day, Reyes was handcuffed and flown out of Florence, Arizona, with other detainees. ICE agents refused to tell him or anyone else where they were going, he said. The plane stopped for a layover — in a state that Reyes still can’t identify — before flying on to the Alexandria Processing Center in Louisiana.

Jeff Migliozzi from Freedom for Immigrants said that this sort of transfer process is increasingly common. Already, many immigration detention centers are at their limits, so “wherever they have beds, they’re sending people,” he said.

“It’s logical that the neighboring states are where they’re transferring people,” Migliozzi continued. “But with ICE, transfers aren’t always logical.”

The day Reyes landed in Louisiana, a friend spotted his car in the parking lot where he had been arrested by ICE. Angela found someone to make her a new car key, then went to pick it up.

San Diego and Louisiana most common points for deportations

At least 1,250 people who were arrested in the San Francisco “Area of Responsibility” this year have been deported, the vast majority to Latin America. Most left the country by bus at the San Ysidro border crossing in San Diego, followed by Alexandria International Airport in Louisiana.

Some 25 percent of all U.S. deportation flights have left this year from the Alexandria Processing Center, with about 10 percent of those arrested locally spending time there.

Reyes was detained in Louisiana for two days. Then, on the morning of July 18, four days after being arrested, agents loaded him and around 100 other detainees onto a flight bound for Guatemala, the second most common destination for all deportees.

About 15 minutes before landing, Reyes said, the federal agents onboard began taking off everyone’s handcuffs. Reyes said that he thought agents did it so that Guatemalan officials would see that “they come nice, without knowing our hands are tied coming into our country.”

Reyes is now staying with his sister and father outside Guatemala City, the capital of Guatemala. He calls his wife and children as often as he can. And, while he will begin looking for legal pathways to return using his wife’s citizenship, he doubts he can return to the United States anytime soon.

Angela, who works two jobs in Daly City, will visit in the fall. But the immigration process for spouses of American citizens can take years if the spouse first entered the United States without documents.

A timeline of Edin Reyes’ journey from arrest to deportation

Source: Reporting by Frankie Solinsky Duryea. Maps by Kelly Waldron.

For his part, Martinez spent much less time detained. After a few hours in the holding cell, he and five other men were handcuffed again, loaded onto another van, and taken to San Francisco International Airport, only a 30-minute drive away. There, the men were split up and loaded onto separate flights.

Martinez’s flight to El Salvador took off at 2 a.m. on June 18, less than 12 hours after he was arrested.

“If this plane ends up crashing,” Martinez remembers thinking, “that wouldn’t even sound that bad.”

The flight landed in San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador. Martinez’s family house, which he hadn’t seen for 14 years, was a four-hour drive away in Nueva Esparta, a small rural town in the northeast of the country.

A timeline of Miguel Martinez Molinas’ journey from arrest to deportation

Source: Reporting by Frankie Solinsky Duryea. Map by Kelly Waldron.

Martinez paid $60 of his cash reserve to take a taxi to his cousin’s house, an hour and a half from the airport. He spent the night there, and then hitched a ride to his old home in Nueva Esparta, what he calls “a mud house in the hills,” that he left because of poverty and hunger.

Martinez said that when he left El Salvador, it was one of the most dangerous countries in the world. He’s now less afraid than he previously was, because of Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele’s crackdown on crime. Even still, he said, he held his backpack closely during the journey home, keeping his $4,500 in savings near.

As soon as he could, he said, he stashed his money in a Salvadoran bank. He withdraws a little cash every week, trying not to keep too much on him at any time.

The conditions in El Salvador are much worse than what he’s used to. “Where I shower, the other day there were a bunch of frogs in there,” he said. Things that he took for granted — AC, safety from bugs and disease, clean roads — are gone.

He bought a used Hyundai for $1,850, to get around the rural area where he lives. After that, rent, and food, he’s left with about $2,000 in savings in late July. He estimates that it’ll last him seven months at best, and he’s trying to find work in the meantime.

The minimum wage in Nueva Esparta is $10 a day. If Martinez wants to be smuggled back into the United States again, the trip would cost $12,000.

“There’s no way I could do that,” he said. His only hope, he believes, is to start his own tire shop. He doesn’t have enough money to do that, so friends back in the United States have set up a GoFundMe. As of July 30, they’ve raised only $180.

Martinez said that he was sad to know that he won’t see his friends and family in the United States again.

“Well, actually I’ll probably see some of them again,” Martinez said, correcting himself. “The ones that are undocumented, they’ll probably end up getting deported, too.”

Methodology

The data used for this analysis was downloaded from the Deportation Data Project, which publishes datasets on ICE arrests, encounters, detainers, detentions and removals. The latest release was published on July 15, 2025 and includes data from September 2023 to the end of June 2025.

The arrests included in the data cover all “administrative arrests,” which are arrests for civil violations of U.S. immigration laws. Those are conducted by ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations, the department responsible for civil immigration arrests within the United States. It does not include arrests made along borders by Customs and Border Protection officers. More on those definitions here.

Want the latest on the Mission and San Francisco? Sign up for our free daily newsletter below.Sign up

There are some duplicates in the arrests dataset and it is not always clear whether those represent multiple arrests or duplicate entries. In our analysis, we assumed that any records that logged an arrest for the same person on the same day were duplicates.

The unique identifiers in the release are the same across datasets. For this analysis, we cross referenced unique identifiers obtained in the arrests data with those in the detentions and removals files. To calculate the total removals, we referenced columns in the detentions dataset as it is more complete. To calculate the number of people still in detention, we calculated the number of unique identifiers that did not have data in the “stay release reason” column. To understand points of departure, we used the removals data.

For any questions, please reach out to kelly@missionlocal.com.

Annika Hom contributed reporting to this article.

MORE ON IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT

Video: ICE officers tackle and detain San Francisco protesters

Asylum-seekers are spending longer and longer at San Francisco’s ICE field office

At least two people detained in S.F. by ICE today. How many more?

Support the Mission Local team

We’re a small, independent, nonprofit newsroom that works hard to bring you news you can’t get elsewhere.

In 2025, we have a lofty goal: 5,000 donors by the end of the year — more than double the number we had last year. We are 20 percent of the way there: Donate today and help us reach our goal!

KELLY WALDRON

Find me looking at data. I studied Geography at McGill University and worked at a remote sensing company in Montreal, analyzing methane data, before turning to journalism and earning a master’s degree from Columbia Journalism School.More by Kelly Waldron

FRANKIE SOLINSKY DURYEA

I’m covering immigration and running elsewhere on GA. I was born and raised in Burlingame but currently attend Princeton University where I’m studying comparative literature and journalism. I like taking photos on my grandpa’s old film camera, walking anywhere with tall trees, and listening to loud music.More by Frankie Solinsky Duryea