Nov. 4, 2023 (SFChronicle.com)

“Oh, what a great day this can be in history!”

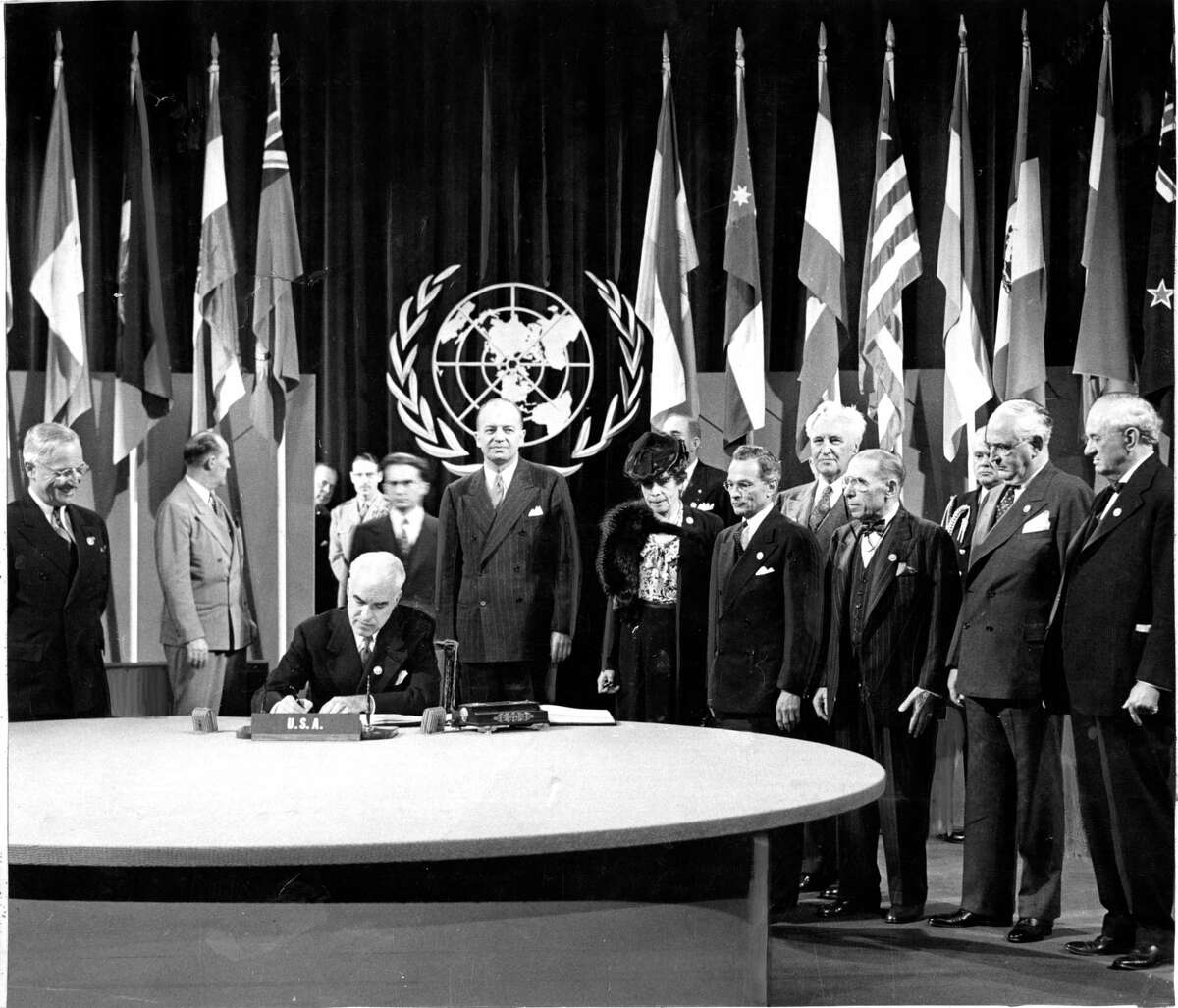

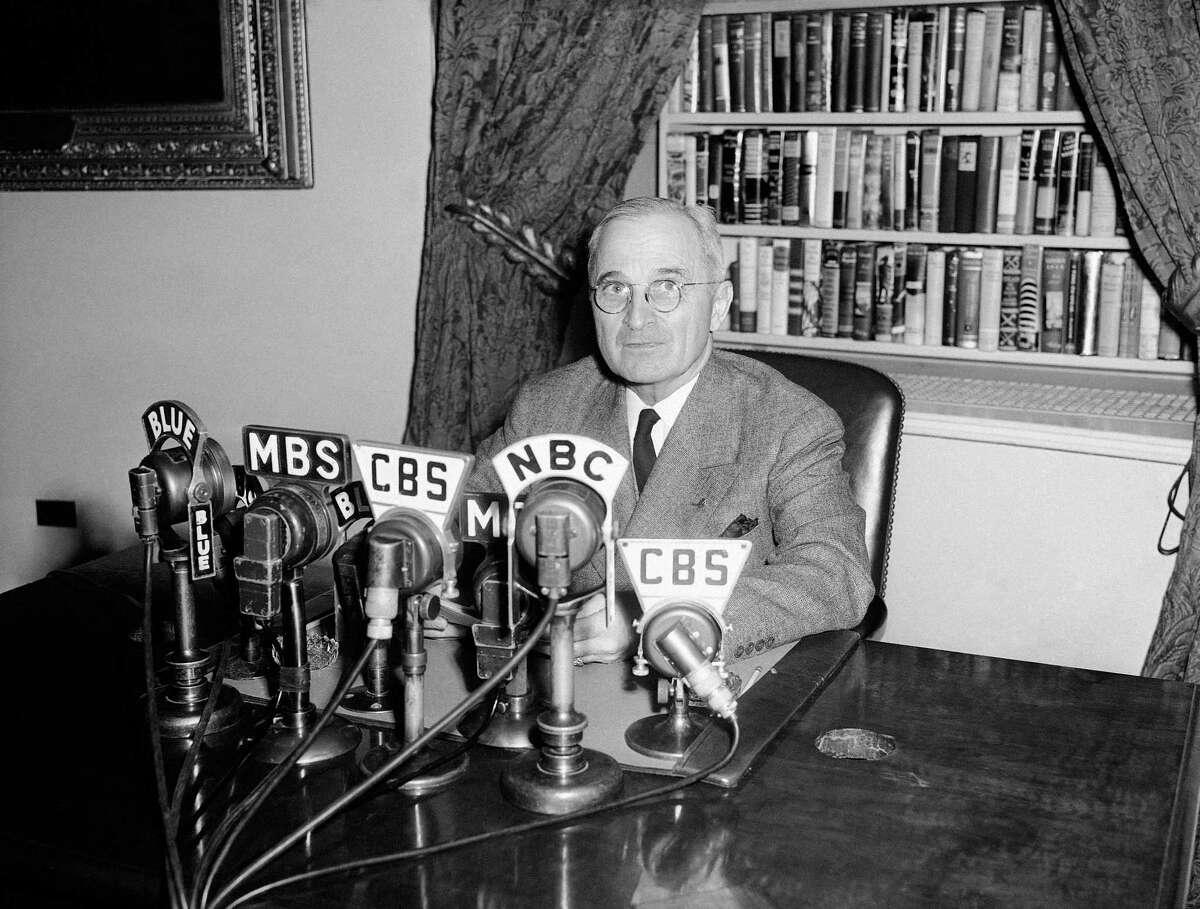

It was one of the most resounding quotes ever spoken in San Francisco, as President Harry Truman watched his secretary of state put pen to paper at Herbst Theatre on June 26, 1945, before the leaders of 50 other countries, and the United Nations was born.

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation conference begins next week, where President Joe Biden and leaders from more than 20 nations will convene to discuss trade, investment and other important issues. It’s the biggest international political gathering to be held in San Francisco since the 1945 United Nations Conference on World Organization. That meeting led to the establishment of the United Nations, created to hammer out a charter and maintain peace and security near the end of World War II.

And yet much of that moment in San Francisco has been lost in history, including the worry of local leaders if the city was ready for the world stage, the tragic mood over the conference and just how close San Francisco came to becoming the United Nations’ permanent home.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been talking about “united nations” — using those words in speeches throughout the war — long before the group was formed. But when Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met in February 1945 to set a date and location, San Francisco was a surprise.

Roosevelt’s staff had quickly settled on the city, because it was geographically more accessible to Asian countries that were less inclined to join, said Alger Hiss, who headed the State Department’s Office of Special Political affairs.

“San Francisco was the ideal choice. It was far removed from the war,” Hiss told the Chronicle in 1970. “It was the most beautiful city of America, and it seemed the center of the world in terms of Japan, China and Europe.”

City leaders, however, were caught off guard. San Francisco Mayor Roger Lapham scrambled, asking for help from East Bay cities and launching a cleanup drive ahead of the event. The pre-conference narrative will be familiar to San Franciscans in 2023 worried about a controversy or disaster that might shine negatively on the city.

More for you

- Will mass protests at APEC disrupt S.F.’s largest international event since 1945?

- Two Bay Bridge lanes will close during APEC. Here’s what you need to know

Except instead of protests from mobs of progressive citizens (the region’s counter-culture movement was still a quarter century away), Lapham was worried about the literal Mob.

“The underworld will be notified in no uncertain terms that more ‘heat’ is on San Francisco,” the Chronicle reported the week before dignitaries arrived, “and that the town must be spic and span from a moral and criminal standpoint long before the conference begins.”

However, even before the event, a pall hovered over the meeting. On April 12, 1945, less than two weeks before the conference, Roosevelt died suddenly of cerebral hemorrhage while sitting for a portrait; he was reportedly half-finished with his opening remarks for the gathering. But former vice-president Truman, in his first big decision as president, announced the conference would continue.

As the first dignitaries arrived before the April 25, 1945, plenary session (a sort of roll call and framing of the discussion), San Franciscans seemed rapt with interest. Hundreds of citizens gathered around Union Square hotels where many of the 850 international delegates and 2,500 members of the press were staying.

Attempts to make the visitors feel welcome were often clumsy. The Chronicle reported Saudi Arabian princes in Golden Gate Park “stood with embarrassed courtesy as cameras clicked and whirred,” and park officials made special note to show the group the zoo’s camels.

But across from San Francisco City Hall, the mood was pensive yet optimistic, as world leaders honored Roosevelt and seemed ready to build on the momentum coming from Europe. (Victory over Hitler’s armies was declared during the conference.)

Chronicle reporter Charles Raudebaugh wrote: “Reverently, dramatically, and with about the same simple dignity that your next door neighbor’s kid went off to fight Hitler, the United Nations Conference on International Organization opened at the San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House.”

The Chronicle’s legendary photographers of the era — including Bob Campbell, Clem Albers and flag-raising on Iwo Jima photographer Joe Rosenthal — were still overseas. But fill-ins, including Corwin Hansen and pioneering photographer Virginia De Carvalho, captured the opera house at its most presidential, with newsreel journalists and their large cameras packed tight in the first balcony.

But the nine-week session to create a U.N. Charter was grueling and not very sensational. It took five hours just to decide who would preside over the meetings. The work stretched out so long that four nations, including war-torn and newly rebordered Poland, joined during the conference. Finally, on June 26, 1945, a finished document was ready.

Truman, who had missed the opening, gave the centerpiece speech before signing the blue-rimmed U.N. Charter with gold lettering.

“You assembled in San Francisco nine weeks ago with the high hope and confidence of peace-loving people the world over,” he said. “Their confidence in you has been justified. Their hope for your success has been fulfilled.”

Truman sent the charter to the United States Senate, where it was ratified by a unanimous vote, and the United Nations formally came into existence on Oct. 24, 1945. San Francisco was its birthplace.

The success of the event made the city the frontrunner to host the U.N. headquarters, and federal officials immediately made the Presidio available. A Chronicle headline called San Francisco “the odds-on favorite as World Capital.” Manhattan was originally ruled out because of space concerns.

But European allies, remembering the long journey by propeller-powered planes — and San Francisco’s lack of a proper international airport, which would arrive nine years later — lobbied for the East Coast. Nelson Rockefeller arranged to sell a spot his family owned along the East River in New York, and in 1949 the current headquarters opened there.

With no U.N. presence today, San Francisco’s role in the creation of the charter is almost entirely historic. There’s a plaque commemorating the United Nations conference on the War Memorial Opera House wall, and international visitors still make requests to see it. And there’s U.N. Plaza, mostly known for a farmers’ market and its controversies surrounding drug-dealing and fenced goods.

But now, nearly 80 years later, San Francisco has another chance to host the world and make history.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated where the U.N. Charter was signed. It was at Herbst Theatre.

Reach Peter Hartlaub: phartlaub@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @PeterHartlaub

Written By Peter Hartlaub

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s culture critic and co-founder of Total SF. The Bay Area native, a former Chronicle paperboy, has worked at The Chronicle since 2000. He covers Bay Area culture, co-hosts the Total SF podcast and writes the archive-based Our SF local history column. Hartlaub and columnist Heather Knight co-created the Total SF podcast and event series, engaging with locals to explore and find new ways to celebrate San Francisco and the Bay Area.