March 20, 2023 (SFChronicle.com)

- On a recent trip to Vietnam, I’m pretty sure I found one key to a happy and harmonious urban life.

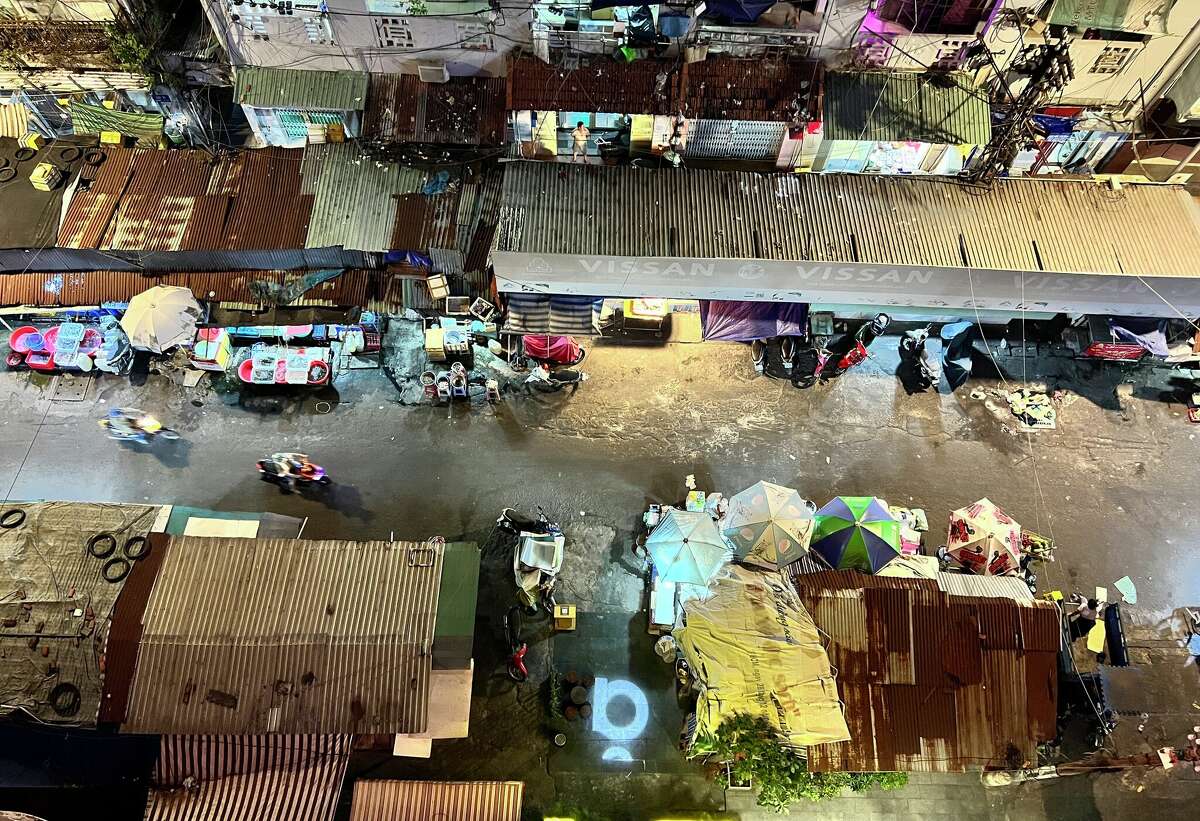

During the drippy, languid hours of midday heat in Ho Chi Minh City, which many also call Saigon, I frequently ducked into every hẻm, or alleyway, that I saw for a little bit of shade. They quickly became my favorite places in the city.

Lined with homes and storefronts that opened up directly into the street, these alleyways were filled with scooter parking, lush potted trees, craft workshops, shrines wafting with incense smoke and baskets of various things for sale. Cars, still a rarity in this city, occasionally snagged parking at alley entrances when they could.

In these alleyways, where the vast majority of residents live, the division between one’s own property and the street is more of a suggestion rather than a rule. Life spills out of the home and onto the streets, where neighbors gather for iced coffee and hang laundry, and generations of restaurateurs cook and serve food right at their own doorsteps.

If that sounds chaotic, it’s not. The ever-present sonic buzz of the city is shockingly absent.

How is this order maintained? Annette M. Kim, a public policy expert and researcher of Vietnam’s sidewalk culture, told me that governance happens at a very local level, with leadership and oversight occurring within neighborhoods. If something works well at the neighborhood level, the city government responds by adapting policies to allow other areas of the city to do the same.

“What’s different about Saigon is that they’ll turn the other way and allow experiments to happen — as long as you’re not making trouble,” said Kim.

That’s so refreshing compared to San Francisco, this uptight city where placing even the most unobtrusive outdoor furniture on the sidewalk usually requires a lengthy permit review process, including detailed site plans, a two-week public notification period and a $1,402 application fee. Even in looser zones, like Slow Streets, the people who use them aren’t allowed to do much with all that space. Sure, you can jog or bike through them, but the infrastructure for actually hanging out isn’t there. During the pandemic was an explosion of parklets, but they’re largely privately owned and not used unless the attached businesses are open.

We do have a few bright spots for unabashed chilling, like Portsmouth Square in Chinatown and Dolores Park in the Mission. And the car-free stretch of John F. Kennedy Drive in Golden Gate Park is starting to perk up with sculptures, a couple of food trucks and chalk murals. Critics, however, continue to emphasize the location’s relative inaccessibility. One solution could be to focus less on JFK and bring the ideals of JFK everywhere in the city: to Bayview-Hunters Point, the Outer Mission and Chinatown alike.

That’s what it’s like in Ho Chi Minh City. Comparatively, American cities like San Francisco, with streets designed for driving, feel like much lonelier places.

There’s data to suggest that isn’t just anecdotal. Even before the pandemic, there was a rash of stories about a “loneliness epidemic” among Americans. In 2021, health care company Cigna reported that more than half of the respondents in a wide survey of American adults said they suffered from consistent feelings of loneliness, including a lack of meaningful relationships and social interaction.

Stories about loneliness usually end with some suggestions on what to do: Put down your phone, reach out to your friends and family, join a club. But what these stories tend to ignore is that loneliness is also a problem of public policy.

Take single-family zoning. A UC Berkeley study of Bay Area cities found that areas zoned for single-family homes were more segregated, with white, high-income residents being more able to access essential resources, including recreational spaces. Cigna’s report mentions that 63% of respondents who earn less than $50,000 a year are lonely, outstripping those who earn more. What use is reaching out to friends if you have nowhere safe, affordable or accessible in your neighborhood to meet them? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the report also found that Black and Latino Americans faced higher rates of loneliness.

Throughout the Bay Area history, there are many examples of how the yearning for community has clashed with the doctrines of modern urban planning. In the 1870s, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors passed a series of ordinances aimed at limiting the public presence of the city’s Chinese population, from restricting where they could live to outlawing the ringing of gongs. More recently, residents of newly built condos in San Francisco’s Mission and in downtown Oakland have fought to shutter clubs and other businesses in historically vibrant neighborhoods, weaponizing noise ordinances and anonymous complaint lines to get their way.

That’s not to say that urban planning should be a complete free-for-all. Having oversight to ensure that disabled people have equal access to the streets and sidewalks is essential, and there should be some checks in place to keep people from, say, installing lava pits on public thoroughfares. Still, it would be great for the city to subsidize the $1,402 application fee to make minor encroachments more accessible to more neighborhoods. Making more community spaces on Slow Streets, like what’s happening on Slow Sanchez, is a great idea.

Kim pointed to the Los Angeles gas stations that transform into bustling taquerias at night as good examples of multifunctional space in cities.

“When you look at a space, don’t just think about it in terms of square meters of concrete,” she said. “It’s space-time. At different hours and on different days, it could become so many different things.”

What I love about the multifunctional Vietnamese alleys is that they are a free and close place to loiter, gossip and meet eyes with other people — to have those chance encounters that characterize places that knit communities together. To me, it feels like an essential part of a “real” city: A dynamic place where all kinds of people are smashed together; a world of unforeseen potential.

I don’t mean to idealize the situation in Vietnam, which has had its own ups and downs. Increased economic development, mostly in the way of foreign investment, is actually pushing places like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City to change. State officials have spent years cracking down on sidewalk vendors in a quest to emulate “modern” cities like Singapore, though they largely failed, meeting resistance from vendors and homeowners alike.

The good news, according to Kim, is that a new generation of city officials and planners are working on ways to preserve the sidewalk’s many functions while making them cleaner and more suitable for transit. “They realized quality of life is important, too, not just economic development at all costs.”

Even Singapore, famously a bastion of extreme order and cleanliness, has asked Kim to suggest ways to bring life back to its streets.

The pandemic gave cities more flexibility in defining public space and how it’s supposed to look. In recent years, San Francisco’s residents have shown that we want more, not less, shared space in our city. We can be ambitious about redefining how our public spaces can function, and San Francisco will only be better for it.

Reach Soleil Ho: soleil@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @hooleil